VIRGINIA BEACH — A special master appointed in a federal voting rights case that is poised to reshape the political landscape in Virginia Beach has recommended a plan that would change the city’s controversial at-large voting system into a system featuring 10 single-seat districts, which sometimes have been referred to as wards.

The plan was filed to U.S. District Court Judge Raymond A. Jackson, and it has been reviewed by both parties in a lawsuit in which Jackson already determined Virginia Beach’s existing local voting system is illegal because it denies minorities the opportunity to select representatives of their choice in violation of the U.S. Voting Rights Act. The current court process is meant to provide a remedy to violations found by the court.

In practical terms, an entirely new voting system is coming to a city scheduled to hold local elections in less than a year.

The special master, voting rights expert Dr. Bernard Grofman, reviewed proposals for new voting systems submitted to the court by the plantiffs and the city. Finding aspects of those plans lacking, he proposes a system similar in concept to 10-district plans that had been submitted by the parties.

The mayor would remain elected by all city voters while other council members would be selected from 10 districts by only the voters who live within those areas.

Grofman’s plan differs in where proposed district lines are drawn, and the court ultimately will decide what to modify and adopt after hearing more from the parties to the suit. It remains uncertain when that decision will come, and an appeal by the city, which is now on hold, is expected to move forward when it does.

“I’m hoping we’re nearing the end of that process,” Deputy City Attorney Chris Boynton said during an interview, noting that the city would work toward implementing any new system ordered by the court while also working on its appeal.

“Time very much is of the essence,” Boynton added.

Virginia Beach has long operated under an unusual voting system in which the mayor and three “at-large” council members are represented by people who can live anywhere in the city while seven other seats are represented by people who must live within geographically defined districts. However, all 11 members of the City Council have been selected by all city voters, even if the members represent district seats. That means people living outside a district have helped determine its representation.

For example, a resident of Pungo, which is within the Princess Anne District, votes for the Princess Anne District representative, but a resident of Bayside also votes for the Princess Anne District representative even though they do not live within that district. Proponents of the system have said it gives all members of the council a stake in the concerns of all citizens and all city voters a voice in every local election.

School Board elections operate similarly, though the lawsuit deals only with the council elections. It is unclear how the case’s ultimate resolution will impact the board.

The existing system is coming to an end. In March, Jackson found that it denies Black, Hispanic and Asian-American citizens a fair say in the electoral process in council races by denying them the opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.

The suit was initially filed in 2017 by Latasha Holloway, an activist who recently announced plans to run for mayor. Georgia Allen, a longtime community leader who led the local NAACP branch for a decade and previously sought office in the city, joined the lawsuit as a plaintiff after it initially was filed. They are represented by the Campaign Legal Center, a nonprofit which was unable to comment for this story due in part to the recent Thanksgiving holiday.

Additionally, changes to state law over the past year, including a bill that was introduced by a local lawmaker, state Del. Kelly Fowler, D-21st District, mean the system in Virginia Beach will need to change anyway because people living outside a district can no longer determine its representation.

Still, only a few short months from the time of year in which candidates normally prepare for fall elections, there is no clear picture of what voting in council or School Board elections looks like in 2022 – or what district boundaries may be.

Grofman’s report essentially considers proposals by the plaintiff and defendant for 10-district plans, while rejecting a city proposal that has been called the 7-3-1 system that would use seven residency districts and three “superwards,” which essentially are larger districts that can encompass smaler ones, similar in concept to the voting system in Norfolk.

All of the proposals were meant to create at least three “minority opportunity districts” to address issues found by the judge. The plantiffs submitted a 10-district plan, and the city submitted its own 10-district plan and the 7-3-1 proposal. A benefit of the latter, some city officials have said, was that it might allow citizens to vote for their mayor and two council members rather than the mayor and only one council member.

Again, in all of the proposals that have been discussed in the court case, all voters in the city would elect the mayor, who serves as one of the 11 members of the City Council.

Grofman reviewed the proposals by the parties and “found that neither plan is responsive to the violations the court found and submitted his own proposed remedial plan,” as Jackson wrote in an order signed on Monday, Nov. 22. In that order, the judge gave both sides 15 days to respond to what the other parties had to say about the remedial plan. The next filings in the case would be expected on Tuesday, Dec. 7.

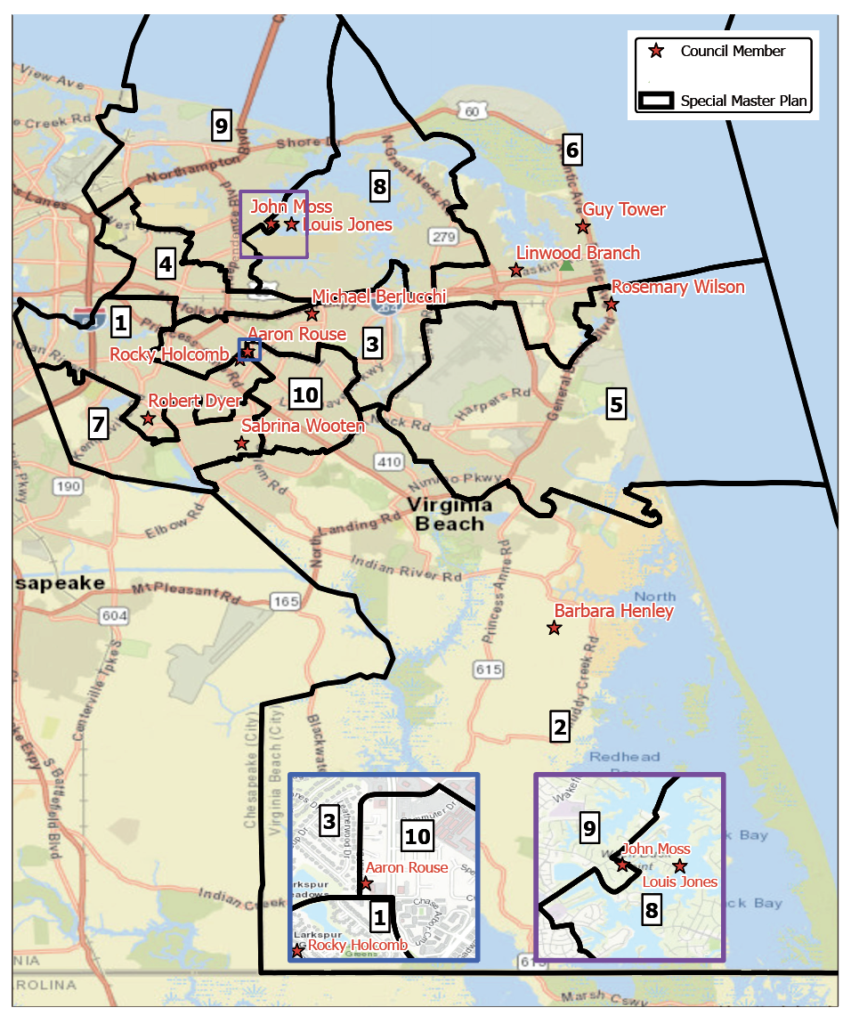

A rendering of the 10-district map as proposed by Grofman can be found at this link, but this has not been adopted by the judge and is not final.

In his report, Grofman noted that the city’s 10-ward plan would place City Councilmember Aaron Rouse, who presently holds an at-large seat on the council and who is one of the two Black people serving on the council, in a district that is majority white. This would make it “unlikely that this minority candidate of choice, who has shown strong support from the minority community but not from the white community, will be able to continue to represent the minority community,” Grofman wrote.

Additionally, two members of the council who are white, Councilmembers Michael Berlucchi and Rocky Holcomb, would be within “heavily minority” districts. Grofman wrote that such a situation “will make it less likely that a minority candidate of choice will be able to prevail in elections in the district, despite the district’s racial demography.” Additionally, the special master noted that Holcomb resides in the same proposed district as Councilmember Sabrina Wooten, who is Black, in the city proposal.

Of the city’s 10-1 proposal, Grofman wrote, “Not only are its three minority opportunity districts inferior to those in the plaintiff’s map, but there are grave defects in how the defendants have reduced minority opportunity by its choices of where to locate incumbents.”

After City Councilmember Jessica Abbott resigned from the Kempsville District seat due to a medical issue, the City Council voted to appoint Holcomb, a former state delegate, to the seat. Holcomb’s residency is considered in the plan drawn up by the special master, which aims to avoid placing incumbents within the same district.

However, the resignation in September of former Vice Mayor Jim Wood from his Lynnhaven District seat led to the appointment of Linwood Branch to that seat, and the special master’s report did not take his residency into account. It is possible Branch and City Councilmember Guy Tower, who represents the Beach District, could end up in the same district.

“We had sent up our maps in before we had the vacancy, let alone the appointment,” Boynton, the deputy city attorney, said.

“We were not trying to put anybody in any districts where they would win or lose,” he said, regarding the city’s aims in preparing its own proposals. “Our goal was trying to draw the districts in a way they were minority-majority districts, not to make life more difficult for any incumbent.”

In its response to the special master’s report, attorneys for the city of Virginia Beach wrote that the special master makes legal errors in his report and argued the report’s findings undercut some aspects of the earlier court ruling.

For example, an element to Virginia Beach’s arguments in the suit and its planned appeal is the idea that Black, Hispanic and Asian-American voters in the city vote cohesively as individual groups and taken as a whole.

The court has accepted that argument by the plaintiffs, Virginia Beach argues, while the city in its filing responding to the special master called this “speculative.”

Grofman’s report says determining how the individual groups vote is “mathematically impossible,” the city notes. Another expert for the city could not draw conclusions about “Asian or Hispanic voting presence in Virginia Beach,” the city argues.

Grofman’s finding “on these topics are sound,” Virginia Beach argues, and the two communities “are too small for purposes of estimating their means of voting preferences by means of statistical analysis.”

The city asks the court to void the ruling and end the injunction on use of the voting system. Barring that, the city asks the judge to clear up the basis of findings in the ruling and adopt the remedial plan so the legal process can proceed.

In its response to the special master’s findings, attorneys for the plaintiffs asked the court to adopt the special master’s district map while modifying the boundaries of one of the districts to include the residence of one of the plaintiffs and also include Burton Station, a historically African-American community that, according to the court, has faced “a documented history of discrimination and neglect by the city.” The special master placed the neighborhood outside a minority opportunity district, whereas the plaintiffs had included it within one of the districts they had proposed.

The plaintiffs also asked the judge to make a factual finding about the cohesion of Black, Hispanic and Asian-American voters and “the presence of a white voting bloc.”

The plaintiff’s arguments take issue with the city’s assertion that the minority groups do not vote cohesively.

A major question that remains is what this means for the School Board, which is not a party in the lawsuit – and whose incumbents apparently have not been included in considerations of where district lines have been drawn in proposed maps.

“There’s more questions than answers,” School Board Chairperson Carolyn Rye, who represents the Lynnhaven District, said during an interview this past week.

Rye said board seats, at present, honor the same boundaries as council seats, as required by law. Currently, the board has four at-large seats and seven district seats. Unlike with the council, the board chairperson is selected by fellow School Board members and not directly by voters.

The 11th seat on the board is a question if a 10-district system is enacted for the council, she noted.

“It has been an odd situation to not be party to a suit that so directly impacts us, too,” Rye said. “While we await the judge’s decision, we’re continuing in talks with our legal counsel, and we’ll have to be made aware of what some of the possible scenarios are.”

Again, local elections in Virginia Beach are less than a year away. “The clock is ticking, so to speak,” Rye said.

© 2021 Pungo Publishing Co., LLC