RICHMOND — Leah Penniman is a bright light with lots to say, and we need to hear her messages about farming, society, justice and our future. I recently met her in Richmond during the Virginia Association for Biological Farming conference, where she inspired, educated and challenged the audience during a keynote address. At various point, I wanted to shout amen, shed a tear, even argue. It was plain terrific.

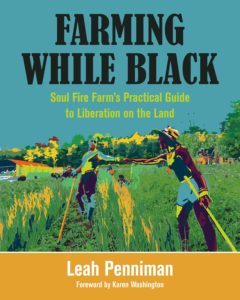

Penniman, an author, educator and farmer, is passionate about organic agriculture and getting that nutrient-dense food to everyone, especially into the food deserts – places where fresh food is not readily available or available at all. Penniman is the co-founder and co-director of Soul Fire Farm in Grafton, N.Y., and author of the recent book Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land.

Penniman is passionate about teaching people how to farm and why to farm – especially young people who seem to need it the most. She is also a scholar who has done the necessary research to speak with authority, and she cares about the story of African Americans in agriculture. And what a story it is.

“Black farmers have contributed substantially to sustainable agriculture,” she told me during an interview. “So everything from [community supported agriculture] to raised beds, cover cropping to pick-your-own have roots in the agrarian tradition, and it’s very important to recognize that to give credit where it’s due, and also to make sure this next generation of black farmers understands that they’re part of a legacy and that they’re not creating something anew. They’re standing on the shoulders of ancestors who have come before. …

“The second thing is to understand that the food system itself is based on exploitation,” she said. “It’s based on stolen land. It’s based on exploited labor. It always has been in this country. It’s all of our jobs to heal and repair the food system.”

We know some parts of the history. We know about slavery and its legacy, which allowed the exploitation of a people in our country and is a history we can never escape but can hope to overcome while understanding its reality.

There is accomplishment, too, we must remember. Most of us have heard of George Washington Carver, the genius who invented so many uses for southern crops to create markets for the impoverished southern black farmers. He inspires me because of how he methodically overcame problems with intellect and spirit, and his solutions helped so many of us.

There are many more stories up to the present of challenge and efforts to overcome them. Some of these are so horrific as to be almost unbelievable, but the horrors of racism, including moments some ignore or acknowledge in only the most glancing ways, are part of American history.

Penniman’s interests all come together in her activism, scholarship and her farming practices. I especially like that she put her messages all together into practical reality by farming at Soul Fire Farm, by truly doing the work. She has been farming organically for 22 years. On her farm, they are doing the important work of carbon-catching soil building, a subject close to my heart and one I have written about here before.

The book is the story of the farm. It combines interludes of historical info as well as tidbits of the heroes and sheroes of black farming communities. You can also read it as a how-to-farm-organically book. It’s all there – good techniques and practices, including some of the widely adapted practices brought here from Africa and used today.

I heard her speak during the conference in Richmond this past month. As some of you know, it is the premier organic farming conference in the state, and, as I wrote here recently, I am involved with the organization. There were many great workshops and good moments. Penniman’s keynote talk and workshop were especially compelling because she added so much history. Her messages challenge us all to look deeper into the full story of our farming past.

“It’s all of our jobs to heal and repair the food system so that farmers get a fair shake, farm workers get a fair shake and consumers get a fair shake,” Penniman said. “We can’t actually do that without paying attention to how race plays into it.”

This includes considering who owns most of the land farmed in the U.S. compared to who does much of the labor, as well as who shares in the bounty of our harvest. People of color are more likely to be living in a food desert and more likely to have diet-related illness, she said. “The great news is our problem is so pervasive, it has many entry points,” she said. “Whether we’re a farmer, an advocate or a consumer, there’s ways we can engage with that.”

I encourage you to read her book because I think our unhealed national wound is worth addressing, and the wealth of sustainable farming knowledge is needed for all Americans in our present.

The stories of community building with sustainable agriculture also play an important part of moving forward for all of us in this increasingly isolated and split society. Agriculture could return to its necessary central role in our communities. Penniman’s work at Soul Fire Farm speaks to that impulse.

Healing wounds and healing the land makes for a powerful combination of ideas. Practical solutions abound for all of us who care about growing healthy food and delivering it to the people.

Wilson, a farmer and consultant who lives in Sigma, writes about sustainable agriculture for The Independent News. Reach him via farmerjohnnewearth@yahoo.com.

© 2019 Pungo Publishing Co., LLC