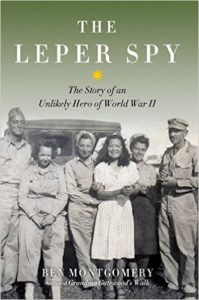

Ed. note — Josefina Guerrero, known as Joey, was a top spy for the Allies during World War II, saving lives while suffering from leprosy during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Author Ben Montgomery tells her story in his new book, The Leper Spy, published earlier this month by the Chicago Review Press. As Booklist wrote, “Montgomery offers a fascinating tribute to the slight Filipina who courageously saved thousands and chose anonymity.” An exclusive excerpt follows.

BY BEN MONTGOMERY

Her body was failing, and she was scared. So little was known about her affliction, and the void was filled with terror.

Though her husband’s main interest was infectious diseases, he knew far more about tuberculosis, which caused some thirty thousand deaths a year in the islands, than leprosy. Mycobacterium leprae was among the first bacilli identified, back in 1873, but it remained a medical mystery. It wasn’t part of the standard medical school curriculum, and few physicians bothered to learn about it. There was no vaccine for leprosy, and no one could say for sure whether it was hereditary or a contagious disease. It was commonly believed that you got leprosy by sharing food or drink with a leper or by touching an infected person.

In the Philippines, leprosy sufferers hid the early symptoms under clothing as long as possible, until it was no longer an option. When the lesions couldn’t be covered, victims were ejected from their communities, becoming charity cases, outcasts, or beggars, forced to leave behind their lives, their jobs, their loved ones. Because of unfortunate wording in the Old Testament, leprosy was regarded in some cultures as a punishment for sinfulness, transforming sufferers’ physical ailments into a moral condition. Stigmatized, they were driven into hellish government- or church-run colonies in the rural provinces, away from society.

There were some eight thousand known cases in the islands at the start of the war, but the chaos of battle had sent many more into hiding for fear they’d become the easiest casualties of the new occupying regime. This was not an irrational fear. In 1912, soldiers in a city in southern China rounded up lepers in their own colony, drove them to a pit, and shot them, women and children included. And then they burned the bodies. Fifty-three people died that day, and the massacre was met with public approval. More recently, in 1937, in the Chinese province of Guangdong, leprosy victims were promised an allowance of ten cents — a ruse — and when they gathered to accept the allotment, more than fifty of them were executed.

The American health authorities in the Pacific Islands adopted a policy of segregation and isolation, shipping the afflicted to far-flung colonies or medical facilities for treatment with an injectable form of chaulmoogra oil, the only drug that showed any promise. With the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, those who weren’t caught and dispatched to leper colonies were now stuck in cities with shuttered pharmacies.

Joey desperately needed medicine to keep her disease under control, but it was virtually impossible to get in the shredded city. Sometimes the drugs could be found on the black market, but the expense was so high, out of reach. So the leprosy ran rampant, attacking her body, destroying her flesh, and causing her joints to stiffen.

She couldn’t just stay at home, in isolation, and waste away. She prayed, sought higher instruction, until one day she had an epiphany. If she believed anything, it was that even the lowliest could be a vessel, could be of service to the greater good. She thought about Joan of Arc, the peasant girl who led France into battle, driving back the English and reclaiming the crown. If she was going to die, she would do so with dignity, face her fate with honor.

In the face of slow death, she decided to use whatever was left to help her people. She approached a friend she knew to be in the underground resistance movement that had formed since Japanese soldiers marched into the city on January 2, 1942. The network was vast, but the guerrillas lived in constant fear. The Japanese army was attempting to purge the city of guerrillas. Soldiers would cordon off a neighborhood, called a zona, and position sentries at every possible entry or exit. They would then call all residents out of their homes and force them to parade past a mole, a Filipino traitor wearing a burlap sack over his head. Known as the “secret eye,” the traitor would indicate with a nod or gesture when a suspected guerrilla passed. The soldiers then pulled that person from the line for questioning. Most never returned home.

Joey knew the risks. Still, she volunteered.

“I want to be a good soldier,” she told her friend.

“Then go underground,” he said. “I will give you a name.”

Her friend gave her the name of a man she knew well from the Ateneo. She was surprised to learn that he was a leader in the underground resistance. She was due for a lot of surprises. She tracked the man down and told him she wanted to work for the resistance.

“We don’t take children,” he told her. She was only twenty-four.

“You’d be surprised what children can do,” she told him. “After all, Joan of Arc was just a young girl — not much more than a child — wasn’t she?”

Montgomery is the author of the bestseller Grandma Gatewood’s Walk. An award-winning staff writer at the Tampa Bay Times, he was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize in 2010.

© 2017 Ben Montgomery. Used with permission.